It's June 27, 2024, and recyclers fill a ballroom at the JW Marriott hotel in Austin, Texas, during the summer convention of the Recycled Materials Association's (ReMA) Gulf Coast Region (GCR). GCR President Becky Proler of SCR Recycling, Houston, is on the stage to announce the historic news that the Smithsonian National Museum of American History will add part of a Prolerizer - the original automobile shred- der-and early archival materials on the shredder to its collection.

The Prolerizer - created in the mid- 1950s by brothers Sammy, Izzie, Hymie and Jackie Proler-was "a watershed invention that revolutionized recycling," the Smithsonian said in a press release announcing the acquisition.

For Becky Proler-daughter of Jackie Proler-the Smithsonian acquisition is more than a source of family pride.

"Thanks to some crazy dream about. getting the Prolerizer in the Smithsonian, metal recyclers have a place in American history," she said to the crowd.

"I believe we're all Prolers today, every one of you. This isn't just about being a Proler. This is about all of us, now and in the future."

To emphasize her point, she asked every attendee to assemble on the stage for a group photo to capture the landmark moment.

That moment was some 70 years in the making, beginning from the day the Proler brothers conceived of their Prolerizer invention in the mid-1950s. Here is that story.

A TEAM EFFORT

We've all heard the saying that "necessity is the mother of invention," and that certainly was true regarding the Prolerizer.

In the mid-1950s, Proler Steel Corp.- the Proler family's recycling business in Houston-had a yard full of ferrous bundles that contained a variety of non-steel materials-porcelain, glass, rubber, wood and nonferrous metals-from old cars, hot water heaters, refrigerators, washing machines and other products in the scrap stream.

Those impurities, which accounted for up to 25% of the bundle weight, were a headache for steelmakers because they reduced each bundle's metal yield in a steel charge and introduced impurities into the steelmaking process.

"At the time, there was no way to efficiently prepare and purify the scrap," said Ronny Proler, Izzie's youngest son. "I'm sure that was one of the driving forces for the brothers to ask, 'How do we process this stuff different and quicker?"

The steel industry reportedly had been seeking a solution to eliminate such "troublesome materials" from the scrap stream for more than 50 years-to no avail.

That "necessity" prompted Sammy Proler to ponder a way to break open the bundles for "decontaminating." As he recounted in a 1998 letter to the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries-now ReMA-the Prolerizer idea came to him in the winter of 1954-1955 on a flight from Salt Lake City to Omaha, Nebraska.

"I thought, 'Why not shred the whole cars into small pieces, then magnetically separate and densify the pieces to increase density for melting?" he wrote in the 1998 letter.

By the time the plane landed in Omaha, Sammy had drawn up a plan of what the plant would look like. When he showed the concept to his brothers and described what the plant would do, "at first they thought I was nuts," he said. "After I convinced them that this is what we should do, then the hard work began." The idea was to use a large ham-mermill to pulverize scrapped products into fist-sized pieces of metal and magnetically separate the steel from the non-steel items downstream. Initially, the Prolers tried to get a U.S. manufacturer to help them turn their shredder dream into a reality, but no one was interested.

"They knew all the reasons why it wouldn't work, but they couldn't convince me," Sammy said in his 1998 letter.

Instead, the Prolers leveraged the wealth of engineering, fabrication and manufacturing talents in the Houston area to build their machine.

"It was a family effort, and it was a team effort that involved many engineers and others who worked day and night to get this thing done," Becky Proler says.

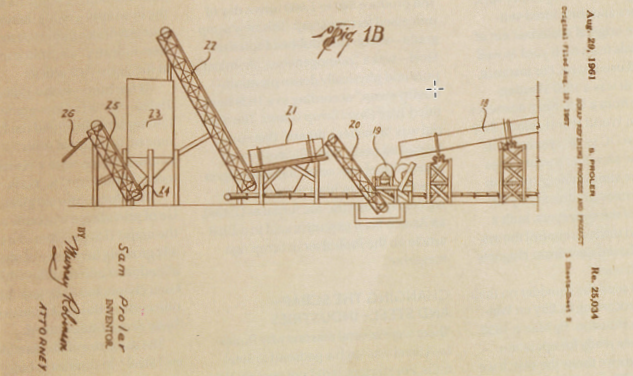

The Prolers and their hired vendors built the original Prolerizer out of scrap materials from their yard as well as purchased used parts. For instance, the power unit was a 1937 Westing- house motor from a U.S. Navy destroyer escort used in World War II, which they rewound from DC to AC synchronous operation. The shredder's wear plates came from the atomic energy plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The family fab- ricated most of the conveyors, built a glass-enclosed tower to control the system and purchased new drum magnets and pedestal cranes.

The Prolers sited the shredder on their new 50-acre processing facility on Wallisville Road in Houston. By March 1958, the shredder was ready for operation.

"The first time we threw the switch we held our breath," Sammy said in his 1998 letter. "We were afraid there would be a monkey wrench in the works somewhere."

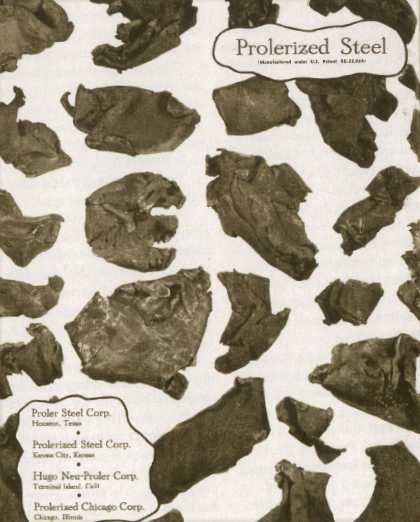

Once the shredder was up and running, the Prolers calculated it could fragmentize a scrap car in 15 seconds and produce 500 to 1,000 tons a day of processed ferrous scrap. This new scrap grade-which they dubbed Prolerized Steel-was a "homogeneous, chemically pure and physically dense premium- quality scrap," according to a 1969 book titled Wall Street Scrap Giants. The mate- rial was "a melter's dream" that could be melted easily and efficiently in all types of steel processes, including open hearths, cupolas, blast furnaces and- especially-electric-arc furnaces (EAFS), an Armco Steel executive said in a 1958 article on the Prolerizer in Scrap Age magazine.

CHANGING THE SCRAP- AND STEEL-INDUSTRIES

There were several reasons why Prolerized Steel was such a godsend to steel mills. For starters, it did not contain the "impurities and nonferrous adulterants" of bundled scrap.

"Now you're looking at filet mignon; you're not looking at 80/20 hamburger," as Ronny Proler puts it.

By resolving that problem, the Prolerizer made it possible to process and upgrade a broader range of low-grade, steel-containing scrap. As a result, the Prolerizer greatly increased "the amount of raw materials available to the steel industry," an Armco executive said in the Scrap Age article.

At the time-in the 1950s and 1960s-the list of low-grade, steel-containing scrap included the huge volume of abandoned vehicles around the country, which were a visual blight and safety hazard on U.S. roads.

"The Proler process gives promise of providing a workable solution to the major U.S. problem of a continually growing inventory of obsolete and abandoned automobiles which have not been channeled back into the production cycle of the steel industry," Wall Street Scrap Giants noted.

The small size of the shredded Prolerized Steel-in contrast to bulky bundles- also made the scrap easier and faster to melt, which sped up a mill's tap-to-tap time and, thus, allowed it to make more scrap heats in a day.

"It allowed the EAFS to go tap-to-tap in 50 minutes instead of several hours," said Bill Proler, Izzie's middle son.

Among the other advantages of Prolerized Steel, "it is easily conveyed and readily stored; can be loaded into electric furnaces without damaging electrodes or furnace linings; and permits a greater scrap tonnage per furnace charge than is possible with most other [scrap] types," according to Wall Street Scrap Giants.

Thanks to these advantages, the Prolerizer "is expected to revolutionize the entire scrap-handling industry and to make possible important economies in the production of steel with scrap as a basic raw material," the Armco executive said in Scrap Age.

In particular, the new shredded scrap promised to have the greatest effect on EAF steelmakers since that sector could use up to 100% scrap in its charges. And developments since then have borne out that prospect, with the EAF sector gaining ground against other steelmaking methods. Prior to 1970, EAFS produced less than 15% of U.S. steel, but today they account for roughly 70% of U.S. output, according to the Steel Manufacturers Association, Washington, D.C.

Though their new Prolerizer and its Prolerized Steel exceeded all expectations, the Prolers decided not to become manufacturers to mass-produce their invention. Instead, they opted to forge joint ventures with recycling companies around the country and built Prolerizer shredders at those operations.

"The brothers never built these to sell," Bill Proler said. "They weren't in the business of selling their invention. They were in the business of joint ventures. Their view was, 'That's not what we do. We're recyclers, and we will always be recyclers."

Based on that philosophy, the Prolers built eight more shredders in the late 1950s and 1960s, joining with recycling partners in Los Angeles; Chicago; Kansas City, Kansas; Everett, Massachusetts.; St. Louis; Jersey City, New Jersey; Philadel- phia; and London. The Kansas City shred- der-installed in 1961-was a joint venture between Proler Steel and local processor I.J. Cohen & Co. Inc. that operated under the name Prolerized Steel Corp. And-as fate would have it--it would be this particular Prolerizer shredder that would make Smithsonian history in 2024.

A PLACE IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Though the Prolerizer had earned its place in scrap industry history simply by being the first patented automobile shredder, how it became part of American history at the Smithsonian is a story that began in March 2023. That's when Becky Proler took a trip to Kansas City, Kansas. She went, in part, to see the Indigo Girls-a longtime favorite musi- cal group-in concert with the Kansas City Symphony and, in part, to visit the Kansas City yard of Advantage Metals Recycling (AMR), which still operated the 1961 Prolerizer.

"The whole weekend was like a flash- back in time," Becky recalled.

During her visit at AMR, Joshua Jones, AMR's regional manager, told her the company planned to decommission the shredder in the summer of 2024. It was difficult to find replacement parts for the 63-year-old shredder-which had processed more than 10 million tons in its lifetime-and it was simply time to replace it with a new machine.

That night, Becky attended the Indigo Girls concert, and the next morning she woke up and thought, "We ought to put the Prolerizer in the Smithsonian. This belongs in a museum."

That next Monday, back in Houston, Becky's first call was to ReMA President Robin Wiener. "I asked what she thought of my Smithsonian idea, and Robin said, 'Why not?' Then we got the ball rolling."

As a first step, Becky asked her cousin Larry Proler to write a letter to the Smithsonian about the Prolerizer. They mailed it to the Smithsonian with a plastic bag of shredded scrap to show what the machine produced. As Becky recalled, Sammy Proler also sent samples of shredded scrap to Lady Bird Johnson in the mid-1960s to show how the Prolerizer was helping her "beautification" efforts around the country-particularly regarding the abandoned car problem.

As it turned out, Becky's letter and scrap ended up on the desk of Kathleen Franz, a curator-and a specialist in car history-as well as chair of the Division of Work and Industry at the National Museum of American History. Franz also looped in fellow curator Abeer Saha, a specialist in engineering topics.

Though Franz receives one or two such query letters each week for inclusion in the national collections, Becky's letter piqued her interest.

"This came in and I thought, 'I really need to follow up on this. This is a water- shed invention that talks about the after- life of cars," Franz said.

So, over the next nine months, Franz and Saha ran Becky's Prolerizer idea through the rigorous Smithsonian vetting process, which included a meeting of Becky, Wiener and Franz in Washington, then a site visit by Franz and Saha to the AMR Kansas City plant to see the Prolerizer in action, followed by a visit to Becky's company in Houston to talk with various Proler family members and see Becky's smaller shredder in operation. What's more, in November 2023 Franz returned to Houston with a colleague from the University of Texas at Austin to conduct oral history interviews with Proler family members.

As a final step in this process, Franz wrote a 10-page report setting out why the Prolerizer history should be added to the national collections and presented it to the museum committee responsible for recommending new acquisitions.

"The case was so strong for this story, and it was such a good match for our environmental history and our car his- tory collections," Franz recounted. "The request sailed through."

In January 2024, Becky got the call. "Congratulations, the decision was unanimous," Franz told her.

The Smithsonian would accept "a representative part of the machine"- specifically, one of the shredder's hammers and early archival materials on the Prolerizer, such as companion photos and engineering drawings, all bequeathed by AMR and its parent company, Nucor Corp., Charlotte, North Carolina.

"By working to document the history of the Prolerizer and its impact on the environmental history of the United States, the museum will tell a number of different stories-from a multigenerational family business to one of problem-solving and innovation," Franz said at the GCR summer convention in Austin, where the for- mal deed-of-gift was signed, transferring the property to the Smithsonian.

Becky was thrilled-and stunned-by the Smithsonian's good news.

"I can't put my feelings into words," she said. "It is so gratifying that they thought enough of this particular innovation to add it to the collection."

Echoing her pride and awe, Ronny recalled, "When I heard that the Prolerizer is going to be in the same museum as the light bulb, telephone and Apple I computer, I went, 'Holy cow, that's his- tory. And it all just came together for me."

According to Franz, "adding the Proler objects, archives and story to the national collections is just the first step in documenting the wider history of recycling in the United States. But it ensures that the story will live on and be available to a wide range of researchers and public audiences through all of our outlets at the National Museum of American History. The Smithsonian is in the forever business, and it's important to have the rich history of recycling in the collections."

As a culmination of the Prolerizer acquisition, ReMA hosted a reception Feb. 26 near the American Enterprise Exhibition at the National Museum of American History. There, Proler family members joined with fellow recyclers, ReMA staff and Smithsonian representatives to view Prolerizer historical items brought out of storage for the evening and to celebrate its addition to the museum's collection. For Becky Proler, that achievement still seems hard to believe.

"I'm just grateful I woke up that morning in Kansas City and decided, 'Why not do this?" she said.

Writer By: Kent Kiser is a freelance writer based in Arlington, Virginia. Previously, he was publisher of Scrap magazine for the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (now the Recycled Materials Association).

metalsrecyclingmagazine.com